What causes the intensification of winter storms over Europe?

Europe is regularly affected by severe winter storms, bringing extreme winds and heavy rain. Different physical processes are important for the development and intensification of these winter storms. Of particular interest is the process of diabatic heating, which is related to the release of heat during cloud and precipitation formation.

It is assumed, that some of the processes relevant to the intensification of winter storms will be affected by climate change. However, it is not yet clear how these processes will interact in a warmer climate and how important diabatic heating will become. It is hypothesized that diabatic heating will become more important in the future, thereby intensifying winds and precipitation (Catto et al., 2019). In order to understand the changing influence of diabatic heating, it is necessary to quantify its contribution to storm intensification. To this end, we have analyzed a selection of historical winter storms.

How does water vapor condensation influence the intensification of storms over Europe?

Using ERA5 reanalysis data (Hersbach et al., 2020), we calculated cyclone tracks from 1997 to 2023 and selected 300 winter storms based on the strongest wind gusts over Central Europe. Our analyses show that, on average, diabatic heating contributes about 25% to storm intensification, and in some cases even more than 70%. Another important process for storm development is the existence of a large horizontal temperature gradient, also known to as baroclinicity. Such a large temperature gradient is typically found where subtropical warm air masses meet polar cold air masses. We use the pressure tendency equation approach (PTE, Fink et al., 2012) to quantify the contribution of individual processes to storm intensification.

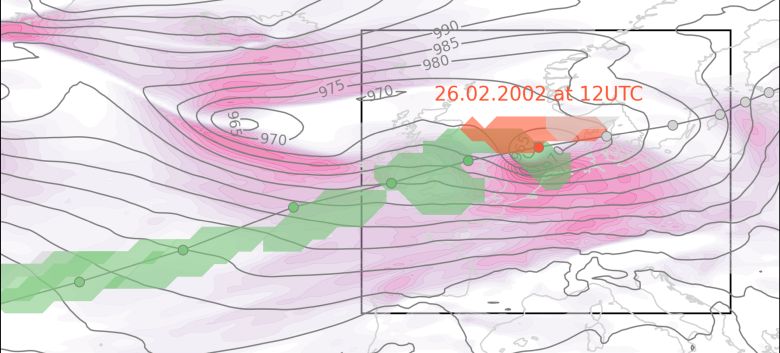

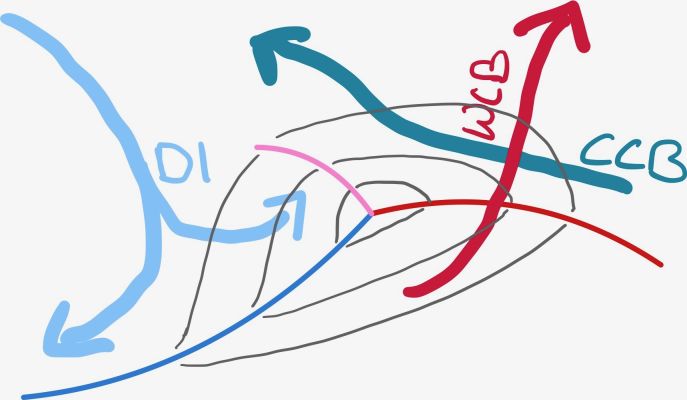

Another important aspect of storm dynamics is the so-called warm conveyor belt (see Fig.1), a rapidly ascending airstream in which additional heat is released through the condensation of water vapor during cloud formation, further intensifying the storm. To identify warm conveyor belts, we used the machine learning model ELIAS2.0 (Quinting and Grams, 2022). Finally, we investigated how the activity of warm conveyor belts varies in storms, quantifying their role in storm intensification.

Structural differences between storms with high diabatic heating contributions

To quantify the differences between storms, we divided our selection of winter storms into three groups (terciles) based on the relative contribution of diabatic processes to storm intensification. We classify those with a low contribution of less than 20% as baroclinic storms, while those with a contribution of more than 32% are classified as diabatic storms.

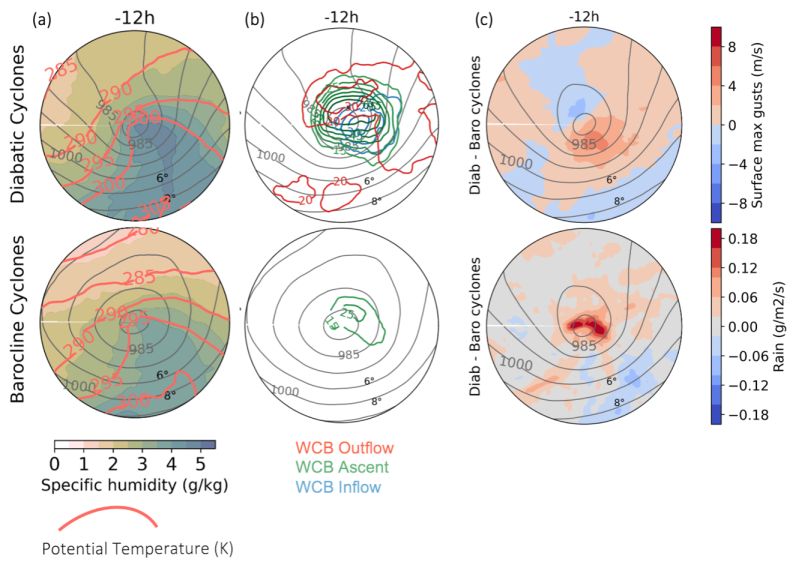

By averaging meteorological fields relative to the storm center, we can identify structural differences between diabatic and baroclinic storms (Fig. 2). Diabatic storms originate further south and move faster. They develop in an environment with higher temperatures and a more humid lower atmosphere (Fig. 2a), particularly in the inflow regions of warm conveyor belts. Increased warm conveyor belt activity (Fig. 2b) and increased diabatic heating promote the rapid intensification of such diabatically influenced winter storms.

Finally, we were also able to demonstrate that diabatically influenced storms are associated with stronger wind speeds, stronger gusts, and more precipitation (Fig. 2c). So, these storms have greater potential to cause damage and can therefore play a significant role in Europe.

The results are published in Christ S, Quinting J, Pinto JG (2025) Characteristics of diabatically influenced cyclones with high wind damage potential in Europe. Quart J R Meteorol Soc https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.70083.

This study is part of the ClimXtreme 2 A6CyclEx Project.

References:

Catto, J.L., Ackerley, D., Booth, J.F. et al.: The Future of Midlatitude Cyclones. Curr Clim Change Rep, 5, 407–420, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-019-00149-4, 2019.

Fink, A. H., Pohle, S., Pinto, J. G., and Knippertz, P.: Diagnosing the influence of diabatic processes on the explosive deepening of extratropical cyclones, Geophysical Research Letters, 39, L07 803, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GL051025, 2012.

Hersbach, H. et al.: The ERA5 global reanalysis, Q. J. Roy. Meteorol. Soc., 146, 1999–2049, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3803, 2020.

Quinting, J. F. and Grams, C. M.: EuLerian Identification of ascending AirStreams (ELIAS 2.0) in numerical weather prediction and climate models – Part 1: Development of deep learning model, Geoscientific Model Development, 15, 715–730, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-15-715-2022, 2022.