Predictability of large thunderstorm systems

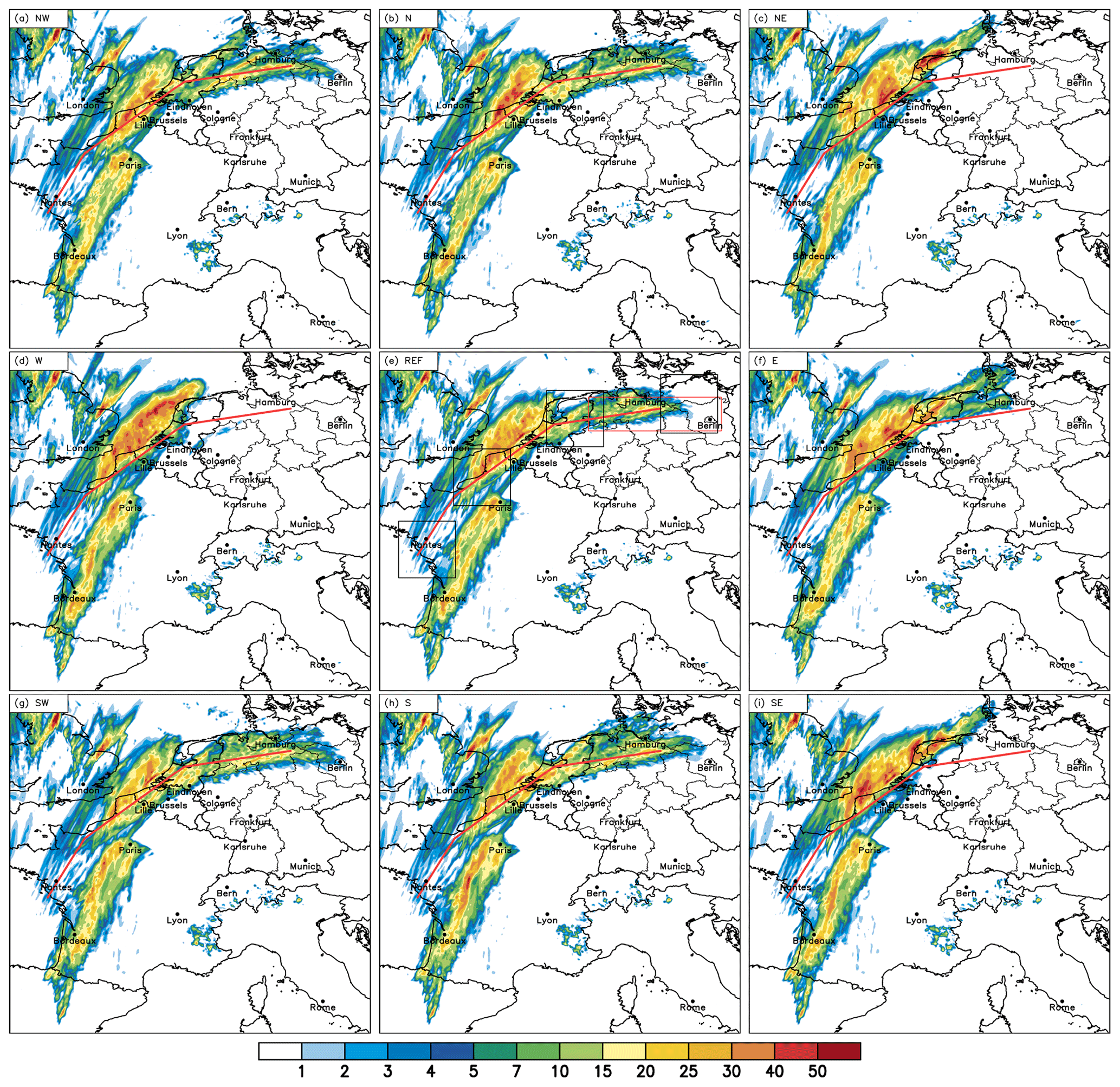

On Pentecost Monday, 9th June 2014, a large Mesoscale Convective System formed over France and later moved over northern Germany. Significant damage resulted in Germany from intense rainfall, strong winds and lightning. Several deaths were also reported in association with the storm. Unfortunately, the forecasts for this day did not indicate any thunderstorms. At IMK-TRO we have performed additional simulations of this case using the German Weather Service’s COSMO model to better understand what happened and how the forecast could have been better. A much larger model domain was chosen covering the entirety of Germany and France and parts of neighbouring countries. This allowed us to capture the entire life cycle of the storm system, which started at the French Atlantic coast and continued until it reached Poland that evening. With this large model domain we were able to simulate the MCS over Germany with approximately the correct timing, location and intensity. However, the success of the simulation was highly dependent on the exact model domain chosen

|

|

|

|

Only five of these simulations successfully represented the MCS over northern Germany, three (NE, W, SE) simulations produced no thunderstorm over Germany whatsoever and one (E) simulation produced some thunderstorms but the intensity and location were not correct. By comparing these nearly identical setups we can determine what causes the differences in the thunderstorms over Germany. The main reason for the difference in the exact track of the MCS during the development stage, and how close the track is to the northern coast of France. On this day there was significant storm potential (high CAPE) inland over France and Germany; however, cooler sea surface temperatures meant that this potential decreased rapidly near the coast. Therefore, simulations where the MCS was only a few kilometers further inland allowed development into large organized thunderstorms (as in the successful simulations) whereas those nearer the coast gradually weakened and dissipated before producing any thunderstorms over Germany. These differences result from minor changes in the timing, location and organisation of the initial thunderstorms near France’s Atlantic coast. These initial differences occur on such small scales that they are not predictable. However, in this case at least, these small changes in the initial thunderstorms determine whether Germany is affected by an MCS later in the day. We can therefore partly attribute the poor forecast for this day to bad luck rather than a poor model. Additionally, the fact that tiny changes to the model domain result in different simulated weather could be utilised to quantify the predictability of a given day. Studies of more cases are needed to determine how useful such an approach could be.

You can read more about our study in this recently published paper:

Barthlott, C. and A.I. Barrett: Large impact of tiny model domain shifts for the Pentecost 2014 mesoscale convective system over Germany, Weather Clim. Dynam. 1, 207-224, DOI:10.5194/wcd-1-207-2020